Why this side quest even exists

Long before ramen took over my bandwidth, I was already deep into noodles. Rice noodles, wheat noodles, hand-pulled, machine-cut, dry-tossed, soup-soaked. One of the earliest constants in that personal noodle archive is char kway teow. Messy, smoky, unapologetically oily when done right.

So when a Penang trip came up, this side quest felt inevitable. Not a single “best char kway teow” hunt, but a cross-section. Street carts, coffee shops, food courts, neighbourhood markets, and stalls with decades of reputation attached to them. The goal wasn’t to crown a winner on paper, but to eat enough bowls back-to-back to understand the range. What changes. What stays stubbornly the same. And where Penang char kway teow quietly draws the line between identity and adaptation.

What exactly is Char Kway Teow, anyway?

Char kway teow looks simple on the surface, but it’s one of those dishes where the margins matter more than the headline ingredients.

Core ingredients you’ll usually see

At its most basic, Penang-style char kway teow revolves around:

- Flat rice noodles (kway teow) as the main starch

- Duck egg for richness and savoury depth

- Garlic and chilli paste as the aromatic base

- Dark soy sauce, used sparingly for colour rather than sweetness

- Prawns, often small but fresh

- Cockles (hum), which contribute a metallic, briny umami when present

- Chinese sausage (lup cheong) for sweetness and fat

- Bean sprouts (taugeh) for moisture and crunch

- Chives (kuchai) for sharpness

- Pork lard, sometimes explicit, sometimes implied

- Caipoh (preserved radish), umami boost with a mix of salty sweetness

Not every plate carries all of these, and that absence is often intentional rather than a flaw.

Regional and stylistic variations

Even within Penang, char kway teow isn’t monolithic.

Charcoal-fired vs gas-fired

- Charcoal-fired – Charcoal produces a more rounded, integrated wok hei. The smokiness doesn’t just sit on the surface; it seems to seep deeper into the noodles and fat. The aroma is fuller, and the heat feels less spiky. When done well, the char becomes part of the flavour structure rather than a top note.

- Gas-fired – Gas fires tend to deliver a sharper, more immediate wok hei. The finish is cleaner and more defined, but the margin for error is narrower. When pushed too hard, the burnt bits can introduce a pronounced bitterness that lingers longer than intended. It can taste aggressive rather than enveloping.

Wet vs dry

- Wet char kway teow – Looser and saucier, sometimes approaching a lightly thickened glaze. It’s less smoke-forward and leans into comfort. In some cases, the “wetness” isn’t added sauce at all, but the result of egg doneness, where softer, less-set egg coats the noodles and pulls everything together.

- Dry char kway teow – This is the default most people picture. Oil-coated noodles, intense wok hei, no visible gravy, with flavour clinging directly to each strand. The emphasis is on fire management and timing rather than cohesion through moisture.

Sweet vs salty

- Sweet-leaning – More commonly associated with Singapore-style char kway teow. Dark sauce is used more generously, contributing both colour and sweetness. The profile is rounder and more immediately accessible, sometimes at the expense of savoury depth.

- Salty-leaning – More typical of Penang. Dark or soy sauce is used sparingly, often more for colour than flavour. The saltiness comes instead from duck egg, Chinese sausage, cai poh, or preserved elements working together rather than a single dominant sauce.

Cai poh or no cai poh

- With cai poh – This tends to skew towards a Teochew-leaning interpretation. Cai poh adds a sharper salty kick and introduces textural contrast. When used well, it creates more layers and keeps the dish from tasting flat or one-note.

- Without cai poh – Cleaner and more straightforward, but also more dependent on egg, sausage, and wok hei to carry complexity. When those elements underperform, the absence of cai poh becomes noticeable.

Big hum, small hum, or no hum

- Big hum – More commonly seen in Singapore. Usually not fully cooked, and prized for its sharp, metallic umami. It announces itself clearly in each bite and can dominate the flavour profile if used generously.

- Small hum – More typical in Penang. Often fully cooked and integrated into the dish. It blends with the wok hei and fat, sometimes disappearing into the background, contributing subtle bursts of umami rather than a pronounced metallic hit.

- No hum – Not uncommon, especially in food court or halal-adjacent contexts. The dish then leans harder on egg, sausage, and fire to compensate for the missing briny dimension.

Batch cooking vs one plate at a time

- One plate at a time – More commonly seen in Malaysia, especially Penang. Each plate is cooked individually, with the cook adjusting heat, oil, and timing for that specific portion. It’s slow, physically demanding, and brutally inefficient, but it allows proper caramelisation, controlled egg doneness, and consistent wok hei. Among die-hard char kway teow fans, this is often considered non-negotiable. It’s not uncommon to hear people say that if it’s cooked in batches, it’s no longer really char kway teow.

- Batch cooking – Unfortunately the norm in Singapore. Multiple portions are cooked together to cope with volume, especially at stalls that sell both fried carrot cake and char kway teow. In many cases, the same flat-top pan used for carrot cake is also used to fry the noodles. From an efficiency standpoint, it makes sense. From a purist perspective, it’s heresy. Heat control becomes blunt, moisture management suffers, and individual plates lose definition. Die-hard fans might faint watching this happen.

The 10 Char Koay Teow I Ate

This isn’t a ramen review in disguise. I’m not breaking down starch hydration, wok temperature curves, or umami layering to the same forensic degree. Char kway teow deserves respect, but I also recognise my own limits. Ten bowls is enough to compare, not enough to claim mastery.

So the approach here is deliberately simpler:

- ★☆☆☆☆ – Hardly passable

- ★★☆☆☆ – Won’t think about eating it again

- ★★★☆☆ – Not too bad

- ★★★★☆ – Pretty good

- ★★★★★ – Worth travelling to eat again

1. Kimberly Street, Roadside Char Kway Teow

Score: ★★☆☆☆

This pushcart sits right at the junction along Kimberly Street, one of George Town’s most photographed night food stretches. Its visibility alone puts it on countless must-eat lists, and the char kway teow here leans into that expectation visually: dark, aggressively charred, and clearly cooked over charcoal.

On the plate, the flavour doesn’t quite live up to the theatrics. It opens very salty, with sweetness arriving only later. Wok hei looks intense but doesn’t penetrate deeply enough to balance the salt. Umami is thin overall, though the small hum, while tiny, tastes decent. The kway teow itself is a highlight: springy, fresh, and well handled. Chilli behaves reasonably. A stall that looks more convincing than it eats.

2. New World Park Food City, Char Kway Teow Stall

Score: ★★☆☆☆

New World Park Food City is a destination built on variety and accessibility. It’s also a common tour-bus stop, largely because there’s something here for everyone. The char kway teow stall reflects that role perfectly: safe, familiar, and broadly appealing.

Seasoning is milder and less salty, with decent umami coming from duck egg and a pleasant sweetness from lup cheong. There are subtle peppery notes, juicy taugeh, and a genuinely good cai poh. Wok hei is minimal, and the fish cake is old and tough. Hum is present but restrained, without the sharp metallic edge. Competent, but clearly designed not to offend rather than to impress.

3. Red Garden Food Paradise, Penang Famous Duck Egg Char Koay Teow

Score: ★☆☆☆☆

Red Garden operates as a night food destination rather than a specialist hawker centre, and its “Penang Famous Duck Egg Char Koay Teow” signage sets expectations high. In practice, this feels more like a branding exercise than a lineage-driven stall.

The chilli is the main problem: powdery, hollow, and aggressively burning with a bitter finish that dominates the dish. Duck egg provides some savoury umami, and the pork lard is actually quite good, but the overall balance never settles. It’s edible, but distinctly off, the kind of plate you stop halfway through not because you’re full, but because something isn’t quite right.

4. Jelutong Market, Kim Hee Cafe, Fei Zai Char Kway Teow

Score: ★★★★☆

Tucked into a coffeeshop near Jelutong Market, Fei Zai Char Kway Teow is firmly a neighbourhood stall. It’s built for regulars, not pilgrims, and the cooking reflects repetition and muscle memory rather than spectacle. When I arrived, they were already closing just before peak lunch.

Wok hei is stronger here, both in aroma and texture. The noodles are springy, with occasional crunchy bits that add interest. It runs quite salty and slightly dry, leaning away from the moist style. Shrimps are small but fresh, cai poh is solid, but the absence of hum leaves the umami profile feeling incomplete. Honest, everyday char kway teow.

5. Gurney Food Hall, Classic Fried Char Kway Teow

Score: ★★☆☆☆

This is mall food court char kway teow, plain and simple. Clean, controlled, and designed to operate within a commercial environment. It often gets mentioned simply because it’s in Gurney Plaza, but stylistically, it aligns far more closely with some nameless Singapore food court char kway teow than Penang street versions.

The kway teow is fresh, tender, soft, and fluffy. Taugeh is limp and a little dry. Prawns are springy but lack flavour. Chilli is balanced and restrained. There’s no hum, no cai poh, and duck egg presence is minimal to the point of being barely detectable. Generic to the core. Put this in a faceless Singapore food court and it wouldn’t raise an eyebrow.

6. New Lane, CHONG Charcoal Seafood Char Koay Teow

Score: ★★★★☆

This is one of Penang’s established char kway teow names, known for its charcoal stove and long queues. I waited about an hour and a half, and the spectacle of the charcoal fire is very much part of the experience. For many, this stall represents a reference point for classic Penang charcoal char kway teow.

The wok hei is even and well distributed, producing a crisp, smoky texture rather than blunt char. Cai poh and Chinese sausage both contribute nicely. It runs salty but controlled. The noodles are thinner than most, springy, and well coated. Duck egg delivers proper umami, chilli is calibrated just right, and surprisingly, it’s not as oily as many other versions. Not lush, but disciplined and confident.

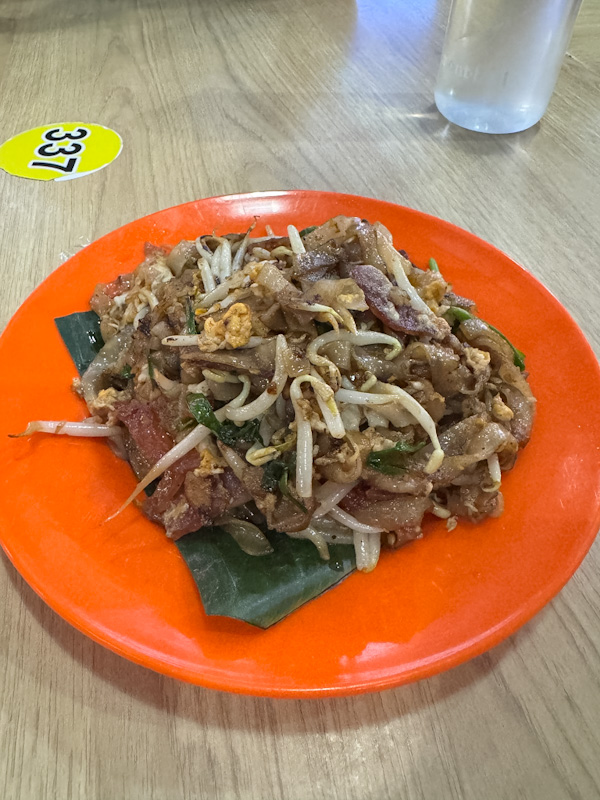

7. Kafe Heng Huat Red Hat Char Kway Teow

Score: ★★★★★

Often referred to simply as “Red Hat,” this stall takes its name from the cook’s signature headwear. She started cooking at a very young age and has always worn the red hat while working. Over time, it became her calling card. Today, her sister cooks alongside her, and the stall is also known as the Sisters Char Koay Teow. If you specifically want her cooking, you order through her helper rather than at the table.

This plate doesn’t rely on hum or cai poh. Instead, it’s about fat control and flavour clarity. Pork lard is fragrant, Chinese sausage brings a rounded sweetness. There’s also peanut-like aroma and taste at times (peanut oil?), and wok hei is confident without being harsh. Egg presence is subtle, almost invisible, but everything holds together. This is the bowl that stayed in my head long after the meal. Worth travelling for.

8. Swee Kong Coffee Shop, Char Kway Teow

Score: ★★★☆☆

Earlier in 2025, Penang held a Char Koay Teow Championship with around 30 participants. The winner, Winnie Ong, runs her stall here at Swee Kong Coffee Shop. As you’d expect, the style leans bold and assertive rather than restrained.

Duck egg is plentiful, salty, and umami-rich. Chinese sausage is very salty but impressively tender. Taugeh is juicy, and wok hei is strong and aromatic. The prawns, unfortunately, are the weakest I had across all ten stalls: springy but clearly characterless, with little flavour. No hum or cai poh here, and the sweet aftertaste is more pronounced. Dry-style, high-impact, and polarising.

9. Ah Leng Char Kway Teow

Score: ★★☆☆☆

Ah Leng came recommended by two Penangite aunties, with a caveat. Many legendary stalls, they said, aren’t what they used to be after ownership passes down. Ah Leng is one such name, now run by his daughter, and whether it still resonates depends very much on personal memory.

Prawns are fine, nothing more. Chilli is the choking kind, making it hard to taste anything else. Taugeh is slim and limp. Small hum adds gentle metallic umami without overpowering. The plate is moist but not wet. Kway teow is firmer and less springy than ideal. Duck egg is present but borderline powdery. Wok hei is controlled, but the soul feels muted.

10. Left Handed Char Kway Teow

Score: ★★★★☆

This stall is known less for its location and more for its technique. The owner cooks with his left hand, earning him the nickname “Left-Handed CKT Dragon” thanks to his fiery wok style. Complicating things further, the stall runs a no-pork, no-lard menu, which makes competing with traditional char kway teow a genuine technical challenge.

Wok hei is strong, bordering on bitter at moments. Taugeh is excellent: fresh, crunchy, naturally sweet. Kway teow is springy, and there’s an almost sourish tang running through the dish that keeps it lively. Small hum delivers a clean, umami sweetness. Proof that skill at the wok can compensate for missing crutches.

Final thoughts

After ten plates in ten days, one thing became very clear very quickly: Red Hat Char Kway Teow is my personal favourite of the lot. Not because it’s the loudest, smokiest, or most stacked with toppings, but because it’s the most composed. It understands restraint. The fat is controlled, the wok hei is confident without turning acrid, and nothing feels added just to prove a point. It’s the plate I kept thinking about after everything else faded. If I had to make a return trip for just one char kway teow, this would be it.

That said, this side quest is very much a snapshot, not a full census. Penang’s char kway teow landscape is too wide, too stubborn, and too personal for that.

Shops I didn’t get to visit (yet)

There were a few stalls I didn’t manage to hit, either because my stomach tapped out or because they required a bit more travelling than this trip allowed. If you’ve eaten at any of these, I’d genuinely love to hear what you think.

- Siam Street Char Kway Teow – Highly recommended by multiple Penangites I spoke to. One of those names that kept coming up unprompted.

- Beng Chin Garden Char Kway Teow – Placed 3rd in the 2025 Penang Char Koay Teow Championship. Clearly doing something right.

- Muscle Man Char Kway Teow – Char kway teow cooked by a hunk. Not everything has to be serious all the time.

- Chulia Street Char Kway Teow – Another pushcart-style stall that people seem oddly loyal to.

- Sisters Char Kway Teow – Often mentioned as the OG sisters setup, distinct from the Red Hat story.

- Ang Boh Char Kway Teow

- Tiger Char Kway Teow

This side quest didn’t turn me into a char kway teow authority, and it wasn’t meant to. What it did do was sharpen my senses and appreciation of what I personally value in a plate: balance over bravado, integration over spectacle, and technique that shows itself quietly rather than shouting.

If you think I missed a crucial stall, or if you strongly disagree with any of the scores here, that’s part of the fun. Eat more. Argue politely. And tell me where I should go next.

hihi!! i really like ur blog and rely on it quite a lot. as a broke student from msia eating ramen here is damn expensive so when i do eat ramen i want to make sure its worth the price. anyways, i have some reccs for when u go to msia for ramen & i’d like to hear ur thoughts if u ever try them!

1. menya appare inside the gardens isetan mid valley (in kl)

– this store is a fav of mine, the tsukemen and the garlic tonkotsu is really good (personally i dont really like the gyoza)

2. menya hanabi (one at sri petaling and another in ss15)

– they specialise in nagoya style mazesoba and i think its damn good (so good that i havent tried any other style of ramen from them…)

3. ramen bankara (mid valley & avenue k)

– i think their ramen is p solid but a bit greasy but their slices of chasu and pork belly is huuuuge (i havent had it in a while)

4. menya shi shido

– this store is the one with all the weird ramen flavours (etc durian ramen but i think that was limited time) but their normal ramen is p good too

5. towzen vegan ramen

– they serve a lot more than just ramen but genuienly some of the best ramen ive ever had, it doesnt feel or taste vegan and the quality is amazing, i think the portion size is a bit small but its 100% worth trying (or i eat too much)

6. seirock-ya (halal)

– i had the tsukemen here and i couldn’t tell it was halal, i think they do an amazing job with their halal ramen

anyways!! if u do read this comment, i highly appreciate and enjoy your blog (please never stop!! unless the sodium and cholesterol gets to you) thank you for your indepth reviews, they really help a broke student like me ^__^

Hi Rei! Your appreciation matters a lot to me! And thank you for your recommendations. I’ll definitely check them out the next time I visit KL again.